A charge had brought the expected fall of coal, but also a trickle of water and, before anything could be done, black damp and stagnant water from the abandoned seams rushed in and flooded the Montagu View Pit. It is regarded as one of the worst mining disasters in Newcastle. The process of recovering bodies from the View Pit lasted until January 1926.

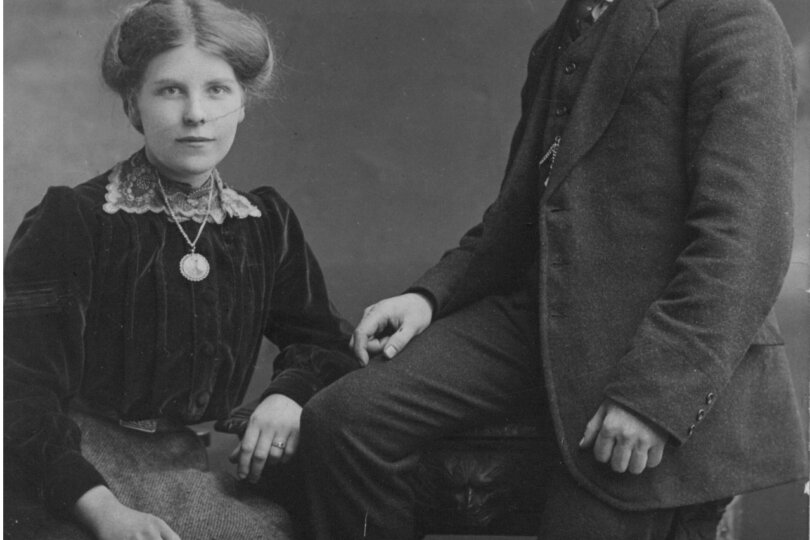

For Ann Jackson, this disaster is remembered in her mother’s collection of family documents and photographs. Her family archive tells the story of her grandfather George Hetherington and his brother, Matthew, who both died that day and were among the last bodies to be recovered. communities, and

George Hetherington

A church leaflet from 1914 records a list of baptisms, marriages, and burials over July and August. Mentioned within it are George Hetherington and Esther Lewins, who were married on August 3rd at St Cuthbert’s Church. Army documents show that George was enlisted in the army in 1915, and transferred to the Army Reserve in 1919, indicating that he likely served in World War 1. His father, Thomas Hetherington, was also a miner. This is evidenced in a64. Birth certificates show that George and Matthew also had another younger brother, Hugh, born in 1900.

Matthew Hetherington

Matthew’s life is documented mostly through photographs in this collection. Although there aren’t any documents evidencing Matthew’s involvement in the army, there are several photographs of Matthew in Army Uniform. Furthermore, within the collection of photographs shared by Ann, there is a photograph of two women, one marked with an X. Writing on the back, written by Ann’s mother, reads “Aunt Jane, Uncle Mattie’s Wife. He was killed in pit with Dad.” Ann also adds that Matthew had a daughter, Sadie. The collection starts to paint an optimistic picture of two young men, having both been involved in the army and surviving World War 1, starting their own families and beginning work in the mines.

After the Disaster

A letter from Mr and Mrs Grantham, dated the third of April 1925, offers sympathy. It is followed by court papers from the 29th of July 1925, awarding Esther and four children – Thomas, George, Ann, and John – compensation after George Hetherington’s death. Thomas was the oldest at age 10, and John was only 1 year old at the time of George’s death.

Thank you letters and receipts for funeral services are dated October 1925, and a small newspaper clipping evidences their bodies having been recovered from the Montagu Pit on October 19th.6 George was soon to be 32 when he died in the pit, and Matthew was 27. It was always said within Ann’s family that their bodies were found with their arms around each other. Ann later found evidence of this in a letter written to her Nana, Esther, and further proof is found in the plan of the bodies held at the Northumberland Records Office.

Copies of the Evening Chronicle are also part of this collection, with tributes to the brothers on the anniversary of the event from 1926 to 1929.

After George’s death, Esther later remarried and opened a shop. This is shown through licences to sell stamps and tobacco, and a photograph of her and her second husband in front of her shop.

The Montagu Pit Disaster had a huge impact on the community, and memorial services are still ongoing, with the 100 year anniversary memorial held in March of this year. The memorial services over time have offered a place for families to come together and share their stories.

The story of George and Matthew Hetherington, preserved in these family documents, shows how family archives can be powerful bridges between personal memory and local history. Viewing the Montagu Pit Disaster through the story of these two brothers offers an intimate connection to the tragedy and reminds us that history and archival collections are made up of personal memories and experiences. When shared, these materials can enrich local history by adding voices often absent from larger archival collections, and ensure that their experiences remain part of our collective memory.

Further Reading

A detailed report of the disaster can be found on the Durham Mining Museum website, at Durham Mining Museum – Montagu View Pit Disaster Report .